Charles H. Davis

Part I: Our Man in Paris

American Impressionist painter Charles H. Davis is rightly credited with establishing a Mystic art colony and what would become the Mystic Museum of Art. But his work, and this museum, may not have existed without the vision of a Paris education in the mind of one of the most New England of poets.

The place in New England was Amesbury, Massachusetts, where Davis was born and raised. The poet was John Greenleaf Whitter, who lived across the street from Davis during the artist’s childhood. Amesbury in that era was known as a center for carriage making. Wishing to help his family, Davis, at fifteen years old, began working in the industry. When he could, he studied art in Boston. Sensing Davis’s passion and talent, however, Whittier urged Jacob Huntington, the wealthy owner of the carriage works and himself a painter, to give Davis the then significant sum of $1,000 to study art abroad. Huntington did as Whittier asked, enabling Davis to study at the Academie Julian in Paris.

Movements in France are directly connected to the art colonies established at the turn of the century in not just Mystic but in Cos Cob and Old Lyme, as artists sought to loose themselves upon the light, seasons, and bucolic and coastal scenery. For Davis, his life was changed at eighteen, in 1874, the first time he saw work by French Barbizon artists, particularly painter Jean Francois Millet. Remembered Davis: “I experienced a conversion” upon seeing Millet’s work, as a “light flash suddenly into a hitherto darkened soul.” Davis studied in Paris for two years, but was able to stay in France for ten, based on the success of his exhibitions back in the states, the first in 1884. After his studies in Paris, Davis settled in Fleury in Barbizon, to refine his aesthetic and to commune with the landscape familiar from paintings. So familiar to him were the scenes depicted, lost once in the dark after a long ramble, Davis gained his bearings by orienting from a tree he recognized from a Millet painting.

Davis exhibited frequently at the Paris Salon and, in 1889, received a silver medal at the Universal Exposition in Paris. In 1890, however, he chose to return to America, searching throughout New England for a waterfront place with stone walls and rocky topography. He settled on Mystic in 1891, in part for its proximity to both Boston and New York, where he and others would sell most of their works. Other artists followed Davis. In 1913, then, he and his second wife, Frances (his first wife, a Frenchwoman named Angele Lagarde, died from illness) along with Dr. George and Mary Reed Leonard, Lorinda Dudley, Elizabeth Mallory, and Rev. Albert Earnshaw formed as the Society of Mystic Artists, although the official founding for the Mystic Art Association date is August, 1914. The Association held its first exhibition of twenty-seven works by eleven artists in 1914, in the former Broadway School on Broadway. An adjacent tearoom provided refreshment. From this debut, the Association grew, with both elected artists and members, studio classes, and exhibitions at sites around Mystic. It is interesting to note that Davis, right around this time, exhibited at the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show. During this early period, the Association’s exhibitions were supplemented by loaned works from William MacBeth and his New York-based MacBeth Gallery, famous as the first gallery to deal solely in American art and for hosting the daring show of The Eight in 1908.

Davis remains the artist most associated with this initial era. Upon his death, The New York Times hailed him as the “Dean of Mystic Painters.” But the most storied figure of this early group would be Henry Ward Ranger, who founded the art colony at Florence Griswold’s rooming house in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Ranger, who had also spent time in Europe, sought out the Connecticut countryside to replicate what he saw and painted in Fontainebleau and the Dutch Lowlands. The leading practitioner of Tonalism, Ranger described his works as “harmonious modulations of color.” At Old Lyme, Ranger fulfilled his dream of forming an American Barbizon but fell out with members over artistic differences. In 1904, he moved to the fishing and shipbuilding village of Noank, Connecticut, and, ultimately, to a home which overlooks Fishers Island Sound and, whose views of Watch Hill, Rhode Island; Fishers Island New York; and Masons Island, Connecticut; take in three states. Ranger exhibited in Mystic Art Association’s early shows but his death, in 1916, prevented him from taking on a larger role in the organization and from becoming more closely linked to the museum.

In his own day, Davis’s work was widely esteemed. To illustrate his lofty stature in the art world, consider the 1922 “smoker” held in his honor by Macbeth Gallery in New York. The event celebrated Macbeth’s thirtieth anniversary with a major Davis show and a black tie dinner attended by 150 of the art world’s leading critics, gallerists, and artists, including Robert Henri and George Bellows. Works by Davis and Ranger are held by some of the premier galleries in the country, including the Smithsonian and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mystic Museum of Art owns Davis’s The Clearing and Summer, and Ranger’s Under the Bough (Mason’s Island, Mystic) in its permanent collection. In 2013, the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, exhibited a major retrospective of Davis’s work, curated to “restore his stature” alongside Childe Hassam, Theodore Robinson, and others in the “pantheon” of the great American landscape painters.

Henry Ward Ranger

Under the Bough

(Mason’s Island, Mystic)

Part II: Better Homes and Gardens

The Association, as can be seen above, began on a solid artistic foundation. The foundation of its new permanent home, however, was fortuitous, ingenious but also surprising: A landfill.

Due to the success of its work, and growing reputation of its artists, the Association in 1928 proposed its first-ever central exhibition space. Members originally planned to utilize a house it owned on Windy Hill. But artist Kenneth Bates discovered that the Rafferty property, an old town dump used since the Clipper Ship era, had been discontinued and was on sale for a low price. Some members, seeing only a refuse strewn lot, opposed. But member Lester Boronda, another key figure in MMoA’s history, persuaded them to look beyond what they saw to what they could create. In 1930, then, the artists of the Association financed a $35,000 bond to purchase the Rafferty land and construct the center. It hired George Fraser, of Providence architecture firm Jackson, Robertson, and Adams, to design it. Before any of that could occur, the property required a cleanup of all the garbage and industrial scale waste that littered the property, including machine parts and derelict streetcars. Horses carted down fill from the relocation of Route 1 and dumped it on the site. Members donated plantings, including Bates, who removed the entire side lawn from his own home to be replanted. Opened in 1931, the center grew to host an array of events including dances, poetry readings, and jazz concerts.

Two significant figures at MMoA during this early period were Bates and his wife Gladys, who devoted themselves to the museum and opened their home to many artists. The two become acquainted at Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and abroad in Rome. Kenneth Bates was a Mystic native. In 1924, he and Gladys chose to move to Mystic permanently, buying the 1729 Burrows Homestead, the town’s oldest home, and establishing a garden based on Giverny, where Ken Bates had visited during Monet’s lifetime. With her training at Cordon Bleu cooking school, Gladys would prepare gourmet meals and foods for openings and museum events. The Bates’ piano was transported back and forth between the museum and their home when necessary. All the while the two continued to be nationally recognized artists. In 1960, Kenneth Bates became a full academician with the National Academy of Design. IBM Corporation selected one of his paintings to represent Connecticut in the 1939 World’s Fair. Gladys won prizes from the Art Institute of Chicago and at the Century of Progress at the Chicago’s World Fair. The permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art includes her work.

“Kenneth Bates,” said artist Harve Stein, himself later an Association president, “Was the fountainhead of nearly every venture the Association undertook.”

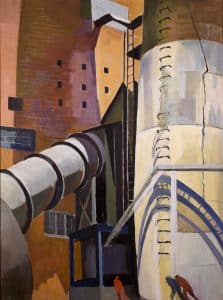

Beatrice Cuming

Industrial Scene, Montville Stacks

Part III: Age of the Illustrators

The first wave of painters to arrive in Mystic were mostly northerners with European experience and sensibility. The second wave, and the next sustaining force in the history of MMoA, followed a different path to Mystic. While many artists flourished and contributed in the years before and after the wars, it is Garrett Price, Harve Stein, Herbert Stoops, Robert Brackman, and Yngve Soderberg, along with Boronda, whose work most defines the era, although it is Brackman who retains the most enduring reputation, for both his own art and for the generations of artists who studied with him.

Price, Stein, Stoops, and Soderberg shared much in common before arriving in Mystic. None came from the East Coast. Stoops was born in Idaho, Price in Kansas, although he later lived in Wyoming. Stein and Soderberg were Chicagoans. All four also studied at the Chicago Art Institute. Stein and Soderberg met while studying in Paris. And all four eventually gravitated to New York City, where they established studios in Greenwich Village and established careers in illustration for publications including Collier’s, Cosmopolitan, and, for Price at least, The New Yorker, where he illustrated hundreds of covers, including one depicting an art hanging at MMoA and another of the Mystic Arts Festival. Stein illustrated classics such as Walden, Little Women, and Treasure Island, and, in 1945, was appointed first-ever head of the Illustration Department at Rhode Island School of Design, retiring as Professor Emeritus in 1976.

As for Brackman, he was born in Odessa, Russia, at ten moved with his family to America, and studied initially at the San Francisco Ferrer School and later at the National Academy of Design. In New York, he studied with two of the great teachers of the period, Robert Henri and George Bellows. In time, Brackman became one of the premier portrait painters in America. The list of his subjects reflects some of the most prominent figures of the era: Charles and Ann Lindbergh, John D. Rockefeller, along with governors, three ivy league presidents, and national military leaders. Yet, Brackman chose not to limit himself to portraits. Despite advice from his friends to focus on portraits for generous remuneration, Brackman felt he could support himself by doing three or four major portraits a year and supplement his income with teaching so he could continue to experiment and paint still lifes and figurative scenes.

The local teaching legacy of artists in this era is extraordinary in scope. Stein taught at Connecticut College, Mitchell College, the New London Art Students’ League, Lyman Allyn Museum, and RISD. Soderberg taught for seventeen years at New London High School. Cuming directed the Young Peoples Art Program at Lyman Allyn Museum for fifty years and taught adults classes at her studio. Brackman taught at the Art Students League, American Art School of New York, Brooklyn Museum, Lyme Academy, Madison Art Gallery Studios, and at his home in Noank, where he would take on 70 to 100 students a summer. Cuming, Stein, Stoops, Soderberg and Brackman all served a tenure as President of the Mystic Art Association.

Beonne Boronda

Part IV: When Tomorrow Hits

The sixties brought change and challenge. Artistically, a new group of artists from Storrs and the University of Connecticut, led by John Gregoropolous and Richard Lukosius, began exhibiting paintings of abstract art, which irritated some of the more academic and traditional members. Gregoropoulos and Lukosius held a two-person show in 1960. Two other key artists in this era were Joseph Gualtieri, of Norwich, who was a long time teacher at Norwich Free Academy and director of Norwich’s Slater Museum, and Lillian Maxwell, who contributed pop art and box construction reminiscent of Joseph Cornell. Indicative of the freedom and daring embodied in the sixties, the Museum’s three traditional shows in 1968 were followed by Synapse ’68, a “happening” in which the “public is invited but there will be no audience” for an event combining actors, dancing, musicians, painters, and guests in a “creative relationship.” Those attending were encouraged to “wear play clothes.”

The biggest change at the Museum, however, arose in 1967, with the opening of Interstate-95, which diverted traffic away from downtown. The arrival of I-95, and succeeding realities, can be seen as part of a larger transformational moment for not just Mystic but the entire region, as commercial supercenters (and later catalogue and online shopping) revised how people shop, rising real estate prices and tourism changed the nature of everyday commerce, new media distracted many from the fine arts, and ever-diminishing art funding in communities and schools eliminated chances for many to visit museums or to discover their creative spirit. All of this inspires Mystic Museum of Art’s commitment to free admission, scholarships, and far-reaching educational outreach.

One of the most colorful, determined, and capable figures spanning several eras, would be Lester Boronda’s daughter, Beonne, pronounced “Bonnie,” a sculptress who played many roles at the Museum and an instrumental role in every single Mystic Outdoor Art Festival, since its inception in 1957. Raised in New York, Boronda began making art at age four, based on impressions of nearby Central Park Zoo, and had her first solo show at age 10. Today, the festival draws tens of thousands to street stalls outfitted for any weather. It also includes activities on both sides of the drawbridge, with childrens events, food stands, and live music. In its first year, however, the festival took inspiration from the one held in New York’s Washington Square and consisted of shop fronts displaying work by artists such as Yngve Soderberg. No nudes were permitted. Originally organized by both the Chamber of Commerce and the museum, the event is now taken on solely by the Chamber.

Boronda won many prizes at Museum exhibitions and served for 20 years as MMoA’s secretary. In addition, she taught six, two-and-a-half hour classes a week at her studio and the Mystic Community Center, until neuralgia and Lyme Disease prevented her from doing so. Sitting in her home on Schoolhouse Road, on Mason’s Island, in 2002, on the occasion of the festival’s 45th anniversary, Boronda told a reporter from The Day newspaper that she attributed her energy to her mix of Irish and Spanish ancestry. She loved the festival, despite the work, because she was a “demon for responsibility.” And to her, it was great fun. “Every so often, you get two artists who get into a fistfight over something, and that’s always interesting,” she said. “One year, there was a disagreement and a woman stiff-armed some very delicate watercolors into the gutter. The paintings ended up with all the rain and bits of ice cream cone floating into the drain. That’s wasn’t too good. That was a job for the cops.”

Katherine Tod

Johnstone, Reflections

Part V: How Soon is Now

The Museum’s modern era began in 1979, the same year the Museum introduced its annual Photo Show, when the Mystic Art Association became an educational non-profit organization, and in 1980, when the board of directors hired Marjorie Ciminera as the first-ever staff member and director, a position she held for fifteen years. From her hiring, the scope of activity at the Museum increased with frequency. In 1981, the membership voted to stay open for five months a year and then, in 1993, with the addition of a climate control system, to be open year round. An 80th Anniversary Campaign, led by Anthony Halsey, raised $300,000 for physical improvements and $100,000 to establish an endowment. As such, the galleries were refurbished with new insulation and electrical system, skylights, acoustical wall covering, track lighting, and refinished floors. Four-hundred people attended a gala reopening. To better protect and document the permanent collection, including records and correspondence, the Dr. Jay W. Constantine Archive Facility was established in 1997, through a gift from Pfizer Inc.

Although MMoA always offered classes in some form, it was not until 1987 that the museum’s board initiated the expansive education program that is a crucial part of MMoA’s identity. The effort was made to “dispel the myth that we were a club” and “branch out to the community,” according to former board member and instructor, Pam Gordiner. Between 1994 and 1998, student participation doubled. Yet talk of a studio building stalled. That is until one day in the winter of 1998, when former museum president, honorary member, elected artist and volunteer Katherine “Kate” Johnstone walked up to then-Board President Anthony Halsey and handed him a check for $125,000, saying “if this doesn’t motivate you, nothing will.” In 1998, the museum hired its first paid-director of education. Then, in 1999, the museum opened the Katherine Tod Johnstone Studios and the Sali Riege Library, adding almost 4,000 square feet to the building and dramatically expanding opportunities for courses, events, and meetings. At the studio’s opening, Johnstone spilled red paint on the floor, wrote her initials, and said: “Have fun.” Alongside a new building came the Visual Thinking Curriculum, through which the museum provided art education to hundreds of teachers and thousands of students. Crucial in this was also the support of the Community Foundation of Eastern Connecticut and the Commission on the Arts.

A name change occurred in 2004, when the Mystic Art Association became the Mystic Arts Center in an effort to reflect the organization’s expansive role in the community. In 2013, the museum received its largest ever donation, when artist Harvey Fuller gifted his home on Bindloss Road in Mystic with the goal that one day it would enable MMoA to finally have an artist-in-residence program.

This time period marks the tenure of executive director, Karen Barthelson, who led the Museum for a decade. Barthelson began as an office assistant in 1998, moved on to become the first-ever full-time Director of Exhibition and Collections, and then became Interim Director and Director in 2006. Key in this period was the decision to eliminate the annual January furniture show, a labor intensive and unwieldy exhibition. Doing so gave the museum flexibility in the winter to curate solo or small group shows and feature sculpture and ceramics. Notable shows included: an exhibition by sculptress Claudia Widdis; Playing with Fire, which featured the work of Jeff P’an, Susan Madasci, and Susan Schultz; and, MAAd Men, featuring abstract artists and University of Connecticut professors John Gregoropoulos, Anthony Terenzio, and Paul Zelanski. Barthelson also curated a retrospective of ceramicist Minnie Negoro. Raised in California, Negoro’s path to Mystic represents a unique story on its own. She learned ceramics during World War II while imprisoned in a Japanese internment camp, when a government program sought to use the workers to make ceramic tableware for soldiers abroad. Negoro went on to earn a degree from the premier program at Alfred University and then, as a UConn professor, to institute the Ceramics major into the Fine Arts Department. She operated a pottery studio in the basement of the William Benton Museum of Art, opened a gallery in Westerly, Rhode Island, and lived for many years on Mason’s Island.

To celebrate its centennial, in 2013, the center organized Mystic as Muse: 100 Years of Inspiration, an exhibition which included works by Davis, Ranger, Childe Hassam and J. Alden Weir. And, in what would be the most significant move since original purchase of a permanent home, MMoA in 2014 bought the beloved “Emporium” building at 15 Water Street in Mystic, a prominent Italianate structure downtown which then underwent a major restoration.

Here it is essential to mention the artist Paul White, the Emporium’s co-owner and a key figure in MMoA’s and downtown Mystic’s history. Like many before involved in MMoA, White studied at Chicago Art Institute and moved to New York City (where he exhibited and sold works at a gallery owned by Candid Camera creator Allen Funt.) In 1965, seeking to leave New York, White traveled to Mystic and discovered a condemned Victorian building, which he and Lee Howard bought and renovated to become the Emporium, the top floor of which became White’s studio. For decades, everything intriguing and exotic found its way to the store, even after White sold the business. In 1972, White moved across the street to a home once owned by Museum co-founder Lorinda Dudley. White dedicated himself to Mystic Art Association, serving as its president and chairman of three Beaux Art Balls, reviving, in 1978, the museum’s tradition of hosting an annual gala featuring costume and wild decoration.

Part VI: Museum Accreditation

MMoA took another step in 2015, when it hired George G. King to become its executive director. Formerly director of the Georgia O’Keefe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the Katonah Museum, in Westchester, New York, King brought unique experience and perspective. In August, 2015, the Board of Directors voted to change the name of the Mystic Arts Center to the Mystic Museum of Art, a change King said “asserts our wishes to conduct all aspects of our business according to the highest professional standards” and communicates to members, funders, and the broad museum audience that MMoA is “elevating the level and quality of all our business.” The following year saw Drawn From a Private Collection, for MMoA an exhibition of unprecedented renown featuring works by George Bellows, Thomas Hart Benton, Georgia O’Keefe, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, and Kara Walker, all loaned from a single private collector. Effective in 2016, after a thorough planning process initiated under former executive director Karen Barthelson, MMoA adopted an ambitious three year strategic plan to enhance MMoA’s identity as a cultural and community resource, to preserve and protect its facilities and grounds, to improve and upgrade gallery spaces, to take steps to insure future financial sustainability, and to reaffirm its central commitment to education, particularly to students in the region’s most at risk schools and communities.

In December, 2018, MMoA was pleased to announce the hiring of Susan Fisher. There is a tremendous excitement about Fisher’s leadership to take MMoA to the final process in becoming an accredited Museum. While there is much work to be done to achieve this accredited status, Susan’s planning and leadership skills make MMoA poised to achieve this next step in its evolution.

In 1913, then, the Mystic Art Association began with a vision of education and artistic daring. It was founded as a society and an exhibition space but it has always also been a community center. In 2018, the museum hosted 20,000 visitors, provided education programs to over 3,000 area school children, and offered courses and programs to 6,700 individuals through lectures, bus trips, studio courses, and other cultural events, while conducting a program of juried and non-juried exhibitions complemented by showings from the permanent collection.

What began as a landfill is now the only downtown public green space on the Groton side of the Mystic River, offering views of the drawbridge, Masons Island, Fort Rachel, shops, working marinas, kayakers and crew teams, and the elements that define downtown Mystic.